Born one year ago from the fruitful encounter of three artists, PatchXR is an engine for creating musical instruments in virtual reality. This intuitive VR tool integrates all the complexity of modular synthesis, while engaging the body in a gestural experience that channels acoustic instruments. We met its creators.

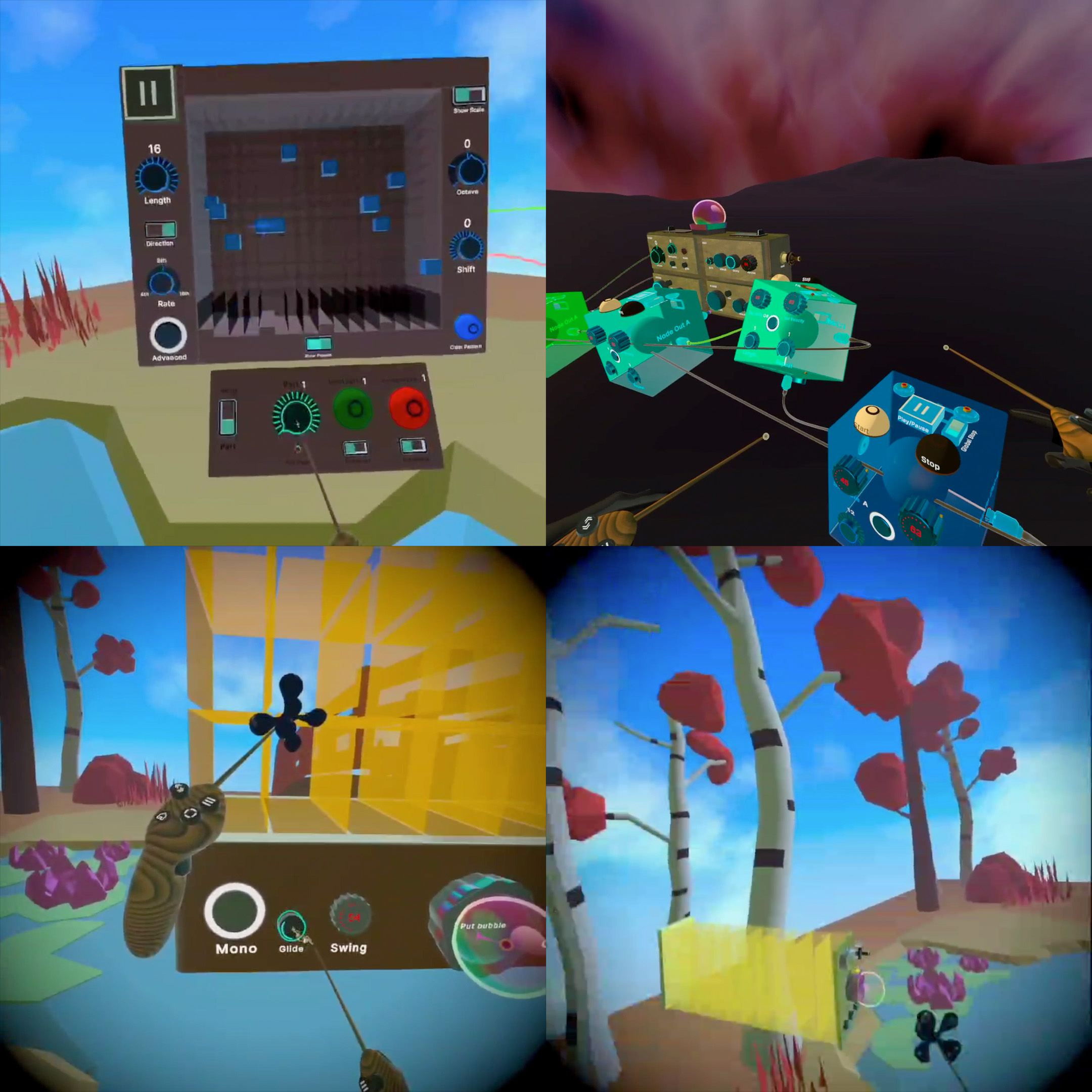

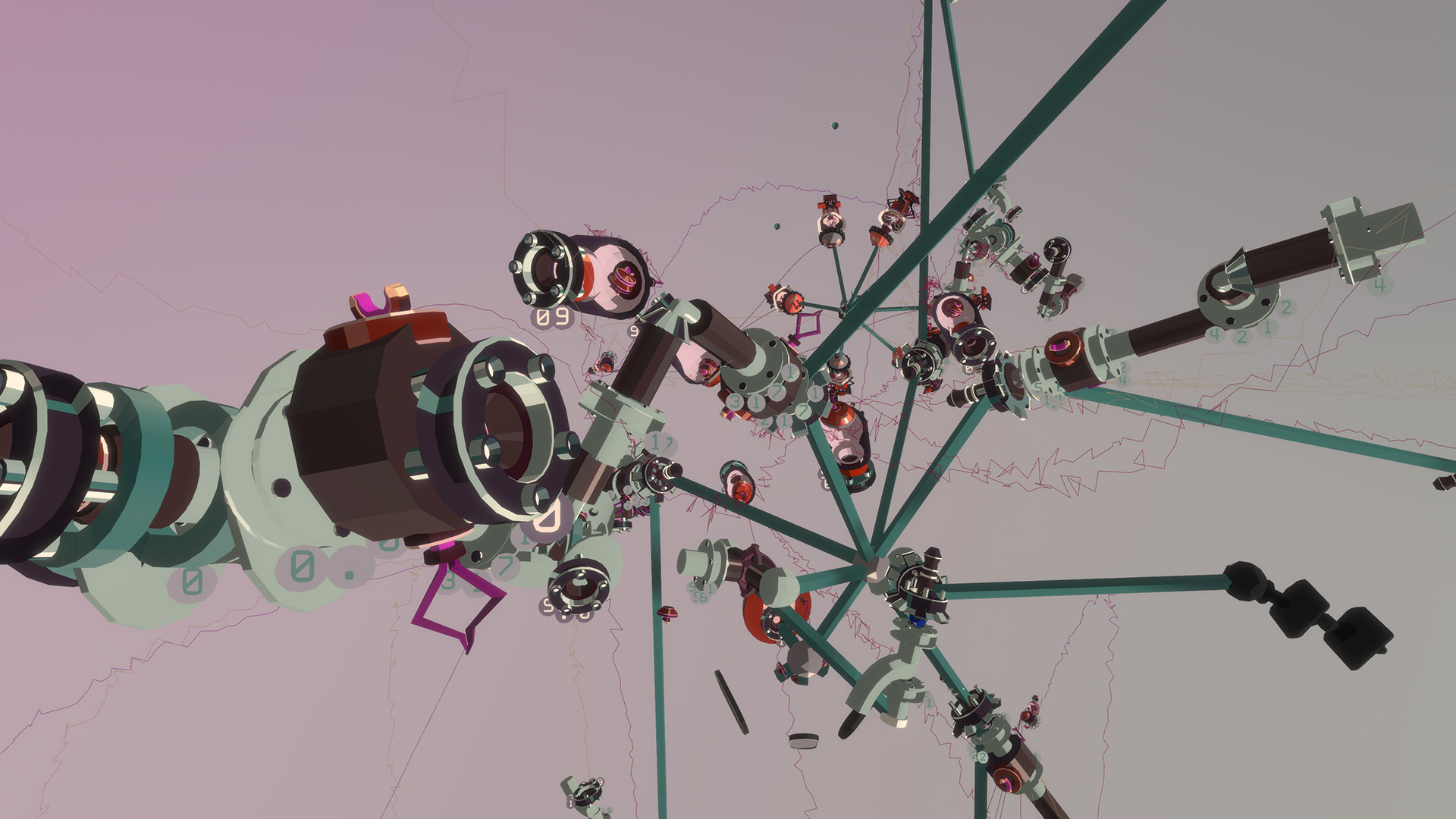

What exactly is PatchXR? Conceptually, it’s a virtual visual programming environment in which users can build and/or play musical instruments. Practically, all you need to do is put on a VR headset to find yourself in an abstract space full of virtual mechatronic-inspired machinery. Rotors, pads, keyboard, modules, speakers will seem familiar to those who have already experimented with modular synthesizers such as PureData or Max. Using magic handles, you interact with the various components. A beat comes into play; you increase the tempo, then slow it down. You hit a few drum pads. Then you trigger another sound and modify its pitch, duration, intensity, tone, envelope, etc. As elements move around inside the space, suddenly your entire body is interacting with them, as if playing a theremin, or better yet, a terpsitone, as you begin to choreograph your soundscape. Soon you have the option of playing with other interfaces/instruments created by the small community of testers who are already using the software. Here a string instrument, like a fountain of water marbles on a harpsichord that you can modulate. Over there, a fat “urchin” of tubes generates a rave sound that has you bobbing your head to the techno rhythms you control. Later it’s a musical automaton or light saber that brings you back to your childhood. An hour later, you’re still at it, like a sugar plum fairy from The Nutcracker in Fantasia.

Starting-up a next-generation VRMI engine

The budding start-up PatchXR was founded in September 2019. The project emerged from an encounter between Eduardo Fouilloux, who since 2017 had been developing the engine for the MuX video game, the artist Mélodie Mousset and the sound engineer Christian Heinrichs. As all three had long been working in immersive media, they were well aware of the opportunities offered by the rapid development and low cost of VR headsets for interactive sound experiences. In a virtual environment, spatialized and procedural sound can be used to direct users’ attention, reinforce the feeling of presence and create a unique immersive experience for each user. PatchXR takes it further by offering virtual reality musical instruments (VRMI) that empower users to compose, play and share this visual, gestural and expressive music in real time, both in virtual and physical space. These instruments enable new techniques for collaboration and ways of interacting.

With MuX, Eduardo Fouilloux had already developed a sandbox for making musical instruments. In 2018, Mélodie Mousset saw him perform at the same festival where she was presenting her work HanaHana: “I was really impressed, especially as sound is such a crucial element in VR to create a lively and immersive experience,” she says. The two kept in touch, and Mélodie described the tool to her collaborators at the time: Victor Beaupuy (artist, musician, game developer) and Christian Heinrichs (musician and procedural sound expert). Their first collaborations were based on voice interaction. That same year, Eduardo released a beta version of MuX on Steam.

“Six months later, the 500 first users had created more than 4,000 instruments, it was incredible,” Mélodie recalls. She was already enthusiastic about the possibility of the teams working together on a project dedicated to creating sounds and visuals. “Chris had developed a PureData compiler with his London-based company Enzien Audio,” says Eduardo. “PatchXR was born the moment we decided to unite all these things under a single vision.”

From expert mode to user mode

In digital synthesizer environments such as Pure Data and Max, users can create, modify and interact with modules—through the keyboard and mouse, or an alternative input method. With PatchXR, users are immersed in a giant space that they can infinitely customize. Based on the principles of modular sound, they can control all the parameters of this virtual world: lights, textures, animation, environment, upload their own meshes and videos. The combinations are endless. “PatchXR uses sound processing algorithms that are similar to those of PureData or Max, but the experience is completely different due to the immersive nature of VR,” Eduardo explains.

In PatchXR, a bit like in Minecraft or with Lego, you can create “sound machines” in real time, by combining simple construction blocks. There are three kinds of blocks: flow components (for processing sound); event components (for triggering events); components to modify the parameter values using motion.

Mélodie explains: “PatchXR is based on modular construction blocks, with steampunk fantasy esthetics. Visually, we didn’t want to simply reproduce virtual synths as we know them—we wanted to invent new forms for each module. Generally, we were looking for a style that was more artistic than technical. The connections are physical: you pick up an oscillator, you pull a cable, you plug in an effect… all this in a zero-gravity environment. You create an instrument like a sculpture, which you can further animate with LFO (low-frequency oscillators), where the animation changes the texture of the sound.”

How to build your instrument in PatchXR

The PatchXR team is already collaborating with some 30 artists. Eduardo has given workshops at Ircam in Paris, at ZHdK in Zurich and at the University of Aalborg. Some people like the performative aspect of the software, while others like to create worlds… In summer 2020, for the A MAZE Playful Media festival in Berlin, the team organized an online hackathon, or rather, “patchathon”. They launched a call for VR projects by musicians, engineers, developers, etc., with the goal of performing an online concert at the end of the festival. They received applications from around the world, including Spain, Iran, Canada, Poland, Colombia, etc. During the 5-day patchathon, participants could appropriate the tool in order to create their own instruments and soundscapes that they would perform for the A Maze audience.

PatchXR is still in development. Currently, it is targeted at a niche audience of designers and sound engineers, or artists who like to experiment with audio synthesis, but the team aims to make the audio procedural, interactive and accessible to all, through an intuitive and playful user mode.

Mélodie says: “Tools such as Fmod and WWise have made it easier to integrate these concepts into video games. We want to empower artists to create directly in these new media formats. Currently we’re trying to encapsulate complex functions, so that we can offer different levels of difficulty. As real-time audio also consumes a lot of energy from the GPU and CPU, we’re working on a light version that would be compatible with the mobile technology of headsets such as Oculus Quest—an intuitive and playful interface that is more accessible to people who aren’t necessarily experts in audio synthesis.”

The PatchXR team believes that their tool pioneers a new genre, somewhere between video game, music and art: “Game engines are becoming so powerful that they’re starting to replace conventional production tools. Concerts in Fortnight or Minecraft with audiences of more than 10 million simultaneous viewers are revolutionizing the music industry. We hope that our engine will empower new generations to express themselves artistically in these new media. The next step is to convince potential users: gamers, musicians, artists.”

Developing the community

One of the team’s goals in the coming months is to install PatchXR stations in universities, in new media art departments, to work in music labs, even VR cinema. The objective is to expand the network of users and gather more user experience feedback.

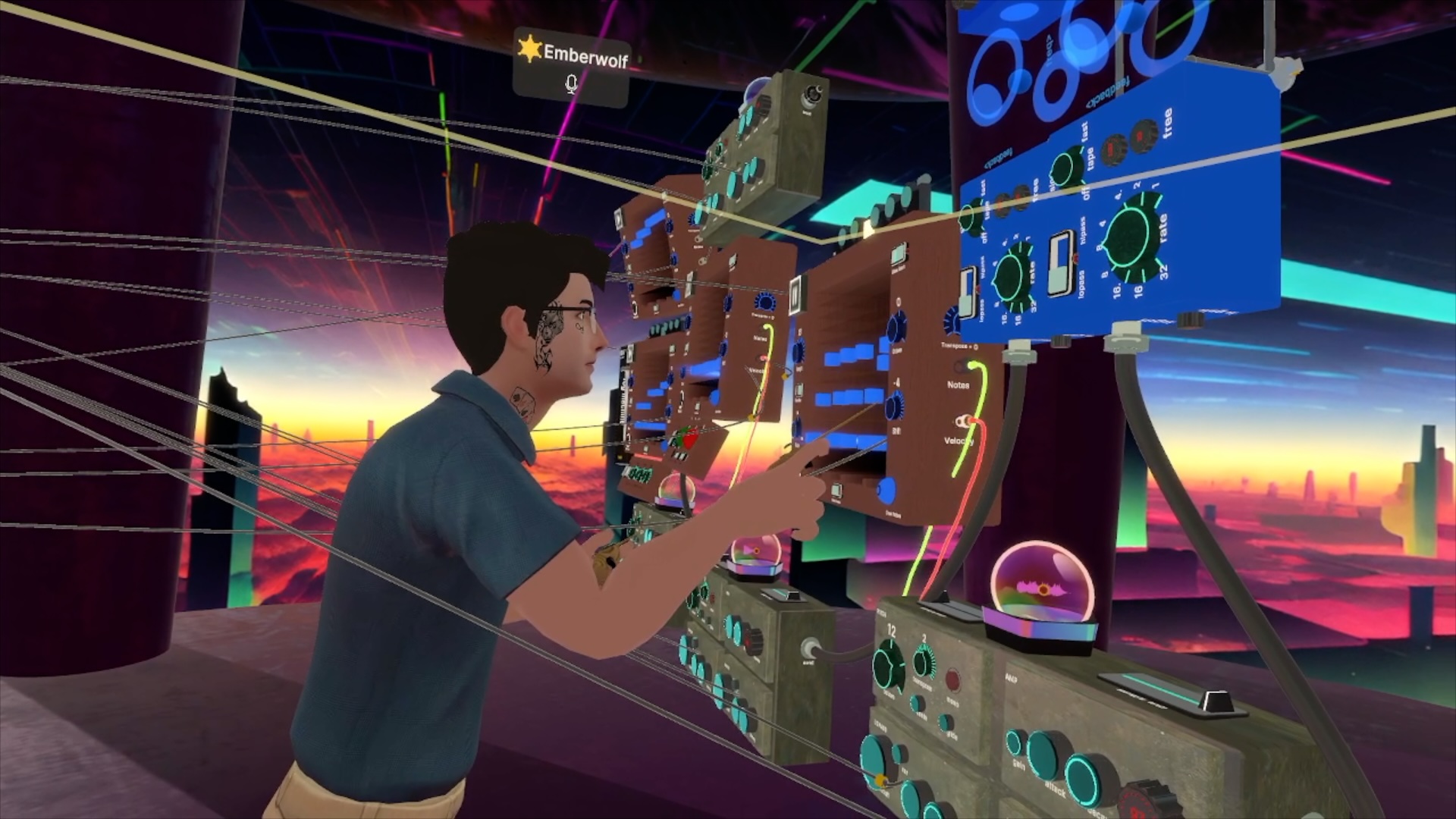

“We want to invite TouchDesigner and Max communities to collaborate within an immersive and playful environment,” says Eduardo. “We’re now focusing our energy on building a platform and a community.” Mélodie adds: “Ideally, people will meet in PatchXR in real-time to make new instruments, play them, and perform for an unlimited audience. How can we collaborate in these virtual worlds? It’s important for it to be connected to the real world.”

The team is currently collaborating with Contrechamps, a contemporary music ensemble from Geneva, and the Liminar ensemble from Mexico, in order to create a prototype for a virtual concert tour. Contrechamps had originally planned to tour Mexico in collaboration with Liminar, before the tour was canceled due to the pandemic. However, the collaboration will still take place through PatchXR online and in virtual reality

“We’re aiming to develop new instruments with these classically trained musicians,” says Mélodie. “They are virtuosos of the clarinet, the violin, the piano, etc. It’s very exciting! We hope to develop a series of online multi-player concerts, mixing virtual and real instruments.”

Serge Vuille, director of Contrechamps, comments: “What will instrumental music be in the future? Is it possible to transcribe in the online digital world these very practiced, extremely precise physical movements that are essential to playing the violin, for example? How can composed music, with all its virtuosity, complexity and refinement, find a path within a virtual environment? These questions are at the heart of Contrechamps’s mission, which is to create instrumental music for the next decade. PatchXR will help us find some answers, and we are enthusiastic about embarking on a journey that could lead to live performances that are appreciated both in a physical concert venue and simultaneously from anywhere in the world via VR. A concert where highly qualified musicians can interpret compositions written specifically for virtual instruments—where the performance is both “live” and replayed in VR, where each audience member can control their own listening experience.”a

Convincing investors

But in order to succeed in this adventure, the PatchXR start-up needs to convince investors. This might have been easier in 2016 or 2017. The public has been slow to adopt VR, and while some applications such as BeatSaber, Tilt Brush and more recently Alyx have emerged, the market remains niche, dominated by an audience of gamers and early adopters.

Still, Mélodie believes that “whether we like it or not, immersive technologies will forever transform the way we interface with digital worlds.” The team remains optimistic for the coming decade, as Eduardo says: “Our target professionals don’t exist yet, or are developing as we speak. We’re not trying to compete with Max or similar tools, we’re trying to introduce an expressive, visual and gestural dimension. By opening our system to OSC, MIDI and Ableton Link, we want to interface with these other digital and physical tools.”

“We launched a start-up,” says Mélodie, “a bit like Unity or Unreal Engine, which are engines for video games. PatchXR is an engine to make musical worlds. We have a technology to offer, and we’re looking for funding. We’re also seeking aid from manufacturers: HTC Vive, Facebook’s Oculus and those involved in spatial computing in general.”

“Spatial computing” refers to a new trend that is a sort of meeting between virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR), also known as Extended Reality (XR). The promise of this new frontier is that eventually, technology will be so seamlessly integrated and interwoven into real and virtual spaces that it will seem to disappear entirely from the user’s experience. Microsoft and Facebook are already investing massively in XR, as Microsoft has released its HoloLens, and Facebook is betting on the integration of AR/XR into everyday life by the late 2020s with technologies that it sees replacing smartphones.

Mélodie concludes: “At some point, we’ll need interfaces that bring our bodies back into the ways that we currently use these technologies. The promise is that we will gradually pull away from screens and regain a certain freedom of movement.”